5/3 notes from class

Wallace Stevens

Anecdote of the Jar

|

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion everywhere.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

anecdote: a short story about an interesting or funny event or occurrence

John Keats’ "La Belle Dame sans Merci"

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow,

With anguish moist and fever-dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna-dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true’.

She took me to her Elfin grot,

And there she wept and sighed full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lullèd me asleep,

And there I dreamed—Ah! woe betide!—

The latest dream I ever dreamt

On the cold hill side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Thee hath in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is withered from the lake,

And no birds sing.

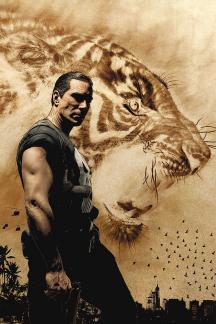

William Blake’s "The Tyger"

|

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

John Donne’s "Death, be not Proud"

Holy Sonnets: Death, be not proud Related Poem Content Details

BY JOHN DONNE

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

and "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning " (metaphysical conceit, p. 1085)

As virtuous men pass mildly away,

And whisper to their souls to go,

Whilst some of their sad friends do say

The breath goes now, and some say, No:

So let us melt, and make no noise,

No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move;

'Twere profanation of our joys

To tell the laity our love.

Moving of th' earth brings harms and fears,

Men reckon what it did, and meant;

But trepidation of the spheres,

Though greater far, is innocent.

Dull sublunary lovers' love

(Whose soul is sense) cannot admit

Absence, because it doth remove

Those things which elemented it.

But we by a love so much refined,

That our selves know not what it is,

Inter-assured of the mind,

Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss.

Our two souls therefore, which are one,

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion,

Like gold to airy thinness beat.

If they be two, they are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two;

Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if the other do.

And though it in the center sit,

Yet when the other far doth roam,

It leans and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.

Such wilt thou be to me, who must,

Like th' other foot, obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end where I begun.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The book records in simple detail all the events and tensions that made up the months that Johnny Gunther fought for his life and his parents sought to help him through recourse to every medical treatment then known. After his last surgery, it was certain that the tumor couldn't be overcome. It had gone deep into his brain. Both his parents knew the end of his life was near, but still had plans for Johnny to spend his summer in the country. Even though no doctor gave him a chance of overcoming the tumor, Johnny was never told that he was dying. In the end, his death came quickly, as a result of the tumor rupturing a blood vessel in his brain. Johnny Gunther died in a hospital, his parents at his side, at the age of seventeen. "Like a thief death took him", his father wrote. He describes Johnny movingly in his coffin: "all that is left of a life!"

Death Be Not Proud takes place in part in contemporary New York City, in the Neurological Institute, and at the Deerfield Academy where Johnny was a student, and at his mother's home in Connecticut. The Neurological institute rises tall above the Hudson River and the George Washington Bridge. Johnny Gunther, a cancer patient, stays in this hospital, on and off, during the last three years of his life. He also stays at the Gerson facility for a time. The family moves him to his mother's home in Connecticut when he is able, he visits his school briefly, to graduate with his class, then dies two weeks later.

Theme

The main theme of this book is how death and illness affect people, and how courage and a commitment to live fully in the face of daily discouragement and frequent setbacks transform such a life, however brief. During the fifteen months that Johnny had cancer, while going through many upheavals that most families do not experience, the Gunther family continued to be grateful he was still alive, and to celebrate that life. Although Johnny died at age 17, the Gunthers were grateful that he had survived as long as he had, and had continued to live as vibrantly and as intelligently as possible.The title of the book, taken from Donne's poem, which ends with a comment on "the death of Death," summarizes this: Death had nothing to be proud of in Johnny's case. His (and his parents') wise, brave choices in living a brief life fully overcame any final destruction of the spirit that a fear of oncoming death might have otherwise wrought.

John 'Papa' Gunther

The journalist, John Gunther, was a devoted father. John is the narrator of this heartbreaking story. He explains his beloved son’s battle with a brain tumor. He made sure to be with his son as often as possible, and to talk with him through his trials. John’s personality was quite subtle and he didn’t express his emotions.

Johnny Gunther

John Gunther, Jr. (1929–1947) was an intelligent teenager living a life too soon aimed towards death. During his struggle with a brain tumor, Johnny studied on his own, received tutoring and took his school's proper exams, including college entrance. He did chemical experiments to follow up on ideas he developed even while ill. Though faced with death he continued to follow his dreams. Johnny was loved for his selflessness and his curiosity about life. He is portrayed throughout the memoir as a brilliant young man who tried with all his strength to defeat his brain tumor.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Robert Frost (p. 1091)

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ode on a Grecian Urn Related Poem Content Details

BY JOHN KEATS

Thou still unravished bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unwearied,

For ever piping songs for ever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd,

For ever panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy'd,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

☆two films that teacher had mentioned☆

1.The Wit(心靈病房 in c)

Vivian Bearing (Emma Thompson) is a professor of English literature known for her intense knowledge of metaphysical poetry, especially the Holy Sonnets of John Donne. Her life takes a turn when she is diagnosed with metastatic Stage IV ovarian cancer. Oncologist Harvey Kelekian (Christopher Lloyd) prescribes various chemotherapy treatments to treat her disease, and as she suffers through the various side-effects (such as fever, chills, vomiting, and abdominal pain), she attempts to put everything in perspective. The story periodically flashes back to previous moments in her life, including her childhood, her graduate school studies, and her career prior to her diagnosis. During the course of the film, she continually breaks the fourth wall by looking into the camera and expressing her feelings.

Late in Vivian's illness, the only visitor she receives in the hospital is her former graduate school professor and mentor, Evelyn Ashford (Eileen Atkins), who reads her excerpts from Margaret Wise Brown's The Runaway Bunny. As she nears the end of her life, Vivian regrets her insensitivity and realizes she should have been kinder to more people. In her time of greatest need, she learns that human compassion is of more profound importance than intellectual wit.

Vivian dies at the end of the film, with her voiceover reciting "death be not proud".

Review

Emma Thompson and Mike Nichols' adaptation of Margaret Edson's intellectual anti-intellectual play "Wit," which won the 1999 Pulitzer Prize, movingly explores a tough but emotionally homeless scholar's confrontation with a life-threatening illness. At the same time, it ruthlessly deconstructs the modern medical research establishment. This excellent film is driven by Edson's sharp dialogue, Nichols' controlled direction and Thompson's riveting, dead-on portrayal of the scholar, with fine supporting performances by the other actors, including a brief appearance by playwright Harold Pinter as her father.English Professor Vivian Bearing (Thompson) is an uncompromising authority on 17th Century English poetry, especially that of John Donne, whose Holy Sonnet X ("Death, be not proud...") figures heavily in the film, an obvious device that could be tiresome in the hands of lesser artists. At age 48, Vivian is diagnosed with Stage IV ovarian cancer by prominent physician Harvey Kelekian (Christopher Lloyd), who gets her to agree to aggressive, debilitating chemotherapy that will serve his research agenda by appealing to their common commitment to rigorous scholarly discipline. The stoic Vivian bears this therapy and degrading study by Kelekian's team, including her own former student Jason Posner (Jonathan M. Woodward). Posner is now a bright research fellow who refers to clinicians as "troglodytes" and whose bludgeoning insensitivity seems to amuse Vivian more than it pains her, at least for a while. Vivian is asked "how are you feeling today?" so frequently and mechanically that it loses all meaning, and she remarks that she's a bit sorry she won't be able to hear herself being asked the question after she has just died. She engages in piercing monologue to the camera, applying the analytical skills she honed as a scholar to her life, her condition and the health care system she confronts. This system ironically sacrifices the well-being of individual patients, not necessarily with their full consent, for the research and professional interests of the physicians who appear to control it--a way of increasing knowledge at a considerable human cost which seems familiar to Vivian. But as her condition grows worse and her fear increases, Vivian starts to question her assumptions about what matters in life.

Unlike much film and television work of recent decades, "Wit" has no interest in deifying physicians, and physicians who see it may object to the blatant disregard for patient well-being and smarty-pants self-indulgence displayed by the research physician characters. The one health care professional who actually cares for Vivian in any real sense is her primary care nurse Susie Monahan, played by Broadway actress and singer Audra McDonald. Susie, who is not an intellectual, simply wants to provide Vivian with health care that is consistent with her professional obligations and with basic human decency, a goal which brings her into increasing conflict with the physicians pushing Vivian's chemotherapy. Despite their differences, the two women form a bond that has important consequences for the apparently friendless Vivian's emotional and physical health. McDonald's performance is steady and subtle, arguably a bit too subtle, but she conveys a fiery core when patient advocacy demands it. The script does not call for Susie to display a great deal of substantive knowledge, and a few other aspects of the film's portrayal of nursing could probably have been improved. Nevertheless, Susie is one of the most powerful feature film portrayals of what a good modern nurse actually does--an added incentive to see a movie that every health care professional should see anyway.

2.The Shawshank Redemption

The Shawshank Redemption is a 1994 American drama film written and directed by Frank Darabont, and starring Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman. Adapted from the Stephen King novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, the film tells the story of Andy Dufresne, a banker who is sentenced to life in Shawshank State Penitentiary for the murder of his wife and her lover, despite his claims of innocence. During his time at the prison, he befriends a fellow inmate, Ellis Boyd "Red" Redding, and finds himself protected by the guards after the warden begins using him in his money-laundering operation.

※warden: the person in charge of a prison

※money laundering : Money laundering is the process of transforming the profits of crime and corruption into ostensibly 'legitimate' assets,In a number of legal and regulatory systems, however, the term money laundering has become conflated with other forms of financial and business crime, and is sometimes used more generally to include misuse of the financial system (involving things such as securities, digital currencies, credit cards, and traditional currency), including terrorism financing and evasion of international sanctions. Most anti-money laundering laws openly conflate money laundering (which is concerned with source of funds) with terrorism financing (which is concerned with destination of funds) when regulating the financial system.

Simply say, the crime of moving money that has been obtained illegally through banks and other businesses to make it seem as if the money has been obtained legally

ostensible:

(1)(外表的,假裝的)appearing or claiming to be one thing when it is something else

(2)appearing to be true on the basis of evidence that may or may not be confirmed

Making a sentence→

The ostensible reason for the meeting turned out to be a trick to get him to the surprise party.

apparent ,outward , external, superficail,

conflate: to combine two or more separate things, especially pieces of texts, to form a whole

sanction: an official order, such as the stopping of the trade,that is taken against a country in order to make it obey international law

Making a sentence→

Many nations have imposed sanctions on the country because of its attacks on its own people.

While The Shawshank Redemption received positive reviews at release, it suffered from poor viewership and competition from other films such as Pulp Fiction at its initial release, and was a box office disappointment. The film received multiple award nominations (including seven Oscar nominations) and highly positive reviews from critics for its acting, story, and realism. Through Ted Turner's acquisition of Castle Rock Entertainment, the film started gaining more popularity in 1997 after it started near-daily airings on Turner's TNT network. It is now considered to be one of the greatest films of the 1990s. It has since been successful on cable television, VHS, DVD, and Blu-ray.

It was included in the American Film Institute's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition).[4] In 2015, the United States Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the National Film Registry, finding it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

In 1947 Portland, Maine, banker Andy Dufresne is convicted of murdering his wife and her lover, and is sentenced to two consecutive life sentences at the Shawshank State Penitentiary. Andy is befriended by contraband smuggler, Ellis "Red" Redding, an inmate serving a life sentence. Red procures a rock hammer and later a large poster of Rita Hayworth for Andy. Working in the prison laundry, Andy is regularly assaulted by "the Sisters" and their leader, Bogs.In 1949, Andy overhears the captain of the guards, Byron Hadley, complaining about being taxed on an inheritance, and offers to help him legally shelter the money. After an assault by the Sisters nearly kills Andy, Hadley beats Bogs severely. Bogs is then transferred to another prison. Warden Samuel Norton meets Andy and reassigns him to the prison library to assist elderly inmate Brooks Hatlen. Andy's new job is a pretext for him to begin managing financial matters for the prison employees. As time passes, the Warden begins using Andy to handle matters for a variety of people, including guards from other prisons and the warden himself. Andy begins writing weekly letters asking the state government for funds to improve the decaying library.

In 1954, Brooks is paroled, but cannot adjust to the outside world after fifty years in prison, and commits suicide by hanging himself. Andy receives a library donation that includes a recording of The Marriage of Figaro. He plays an excerpt over the public address system, resulting in him receiving solitary confinement. After his release from solitary, Andy explains that hope is what gets him through his time, a concept that Red dismisses. In 1963, Norton begins exploiting prison labor for public works, profiting by undercutting skilled labor costs and receiving bribes. He has Andy launder the money using the alias Randall Stephens.

In 1965, Tommy Williams is incarcerated for burglary. He is befriended by Andy and Red, and Andy helps him pass his GED exam. In 1966, Tommy reveals to Red and Andy that an inmate at another prison claimed responsibility for the murders for which Andy was convicted. Andy approaches Norton with this information, but he refuses to listen and sends Andy back to solitary confinement when he mentions the money laundering. Norton has Hadley murder Tommy under the guise of an escape attempt. Andy declines to continue the laundering, but relents after Norton threatens to burn the library, remove Andy's protection from the guards, and move him to worse conditions. Andy is released from solitary confinement after two months, and tells Red of his dream of living in Zihuatanejo, a Mexican coastal town. Red feels Andy is being unrealistic, but promises Andy that if he is ever released, he will visit a specific hayfield near Buxton, Maine, and retrieve a package Andy buried there. He worries about Andy's well-being, especially when he learns Andy asked another inmate to supply him with six feet (1.8 meters) of rope.

The next day at roll call, the guards find Andy's cell empty. An irate Norton throws a rock at the poster of Raquel Welch hanging on the cell wall, revealing a tunnel that Andy dug with his rock hammer over the last 19 years. The previous night, Andy escaped through the tunnel and prison sewage pipe, using the rope to bring with him Norton's suit, shoes, and the ledger containing details of the money laundering. While guards search for him, Andy poses as Randall Stephens and visits several banks to withdraw the laundered money, then mails the ledger and evidence of the corruption and murders at Shawshank to a local newspaper. FBI agents arrive at Shawshank and take Hadley into custody, while Norton commits suicide to avoid his arrest.

After serving forty years, Red is finally paroled. He struggles to adapt to life outside prison and fears he never will. Remembering his promise to Andy, he visits Buxton and finds a cache containing money and a letter asking him to come to Zihuatanejo. Red violates his parole and travels to Fort Hancock, Texas to cross the border to Mexico, admitting he finally feels hope. On a beach in Zihuatanejo he finds Andy, and the two friends are happily reunited.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

★ Vocabulary Box★

1.synecdoche(提喻法)a word or phrase in which a part of something is used to refer to the whole of it, for example, "a pair of hands" for "a worker" or the whole of something is used to refer to a part ,for example, " the law" for "the police officer"2.conceit:

A. far-reached comparison

(1) a result of mental activity

(2)individual opinion

(3)favorable opinion; especially excessive appreciation of of one's own worth or virtue

B.a fancy item or trifle

For example→Conceits were fancy desserts, made either of sugar … or pastry. — Francie Owen

C.a fanciful idea

an elaborate or strained metaphor(=a far-reached comparison)

The poem abounds in metaphysical conceits.

3.metaphysical

4.ode:a lyric poem usually marked by exaltation of feeling and style, varying length of line, and complexity of stanza forms

For example: Keats's "Ode To a Nightingale”

5.lull: to cause to sleep or rest(=soothe )

6.much less: and certainly not

Ode To a Nightingale

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy,

Though the dull brain perplexes and retards:

Already with thee! tender is the night,

And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne,

Cluster'd around by all her starry Fays;

But here there is no light,

Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown

Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast fading violets cover'd up in leaves;

And mid-May's eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call'd him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn;

The same that oft-times hath

Charm'd magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Figures of speech used

Allusion

The nightingale alludes to Philomela, a character in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, who was turned into a nightingale by the Gods to escape death from the hands of her rapist.

In line 4, the words “lethe wards” allude to the river of forgetfulness, Hades in Greek afterworld that caused memory loss in people that drank water from it.

In line 7, the bird alludes to a female spirit in Greek mythology when it is called a “light-winged Dryad.”

In line 16, the drink alludes to the spring “Hippocrene” that in Greek myth was created by the stamping of the winged horse, “Pegasus.”

In line 32, the poet alludes to the Greek God of wine, “Bacchus” as not responsible for his fanciful escape.

In the lines 63 66, Keats alludes to the Biblical figure, “Ruth” as being a listener of the magnificent song of the nightingale.

Personification

In line 16, the drink is invested living characteristics when it is referred to as “blushing.”

In lines 25 26, the disease “Palsy” is depicted as someone menacingly powerful, capable of causing seizures in men.

In lines 29 30, both “Beauty” and “Love” are said to lose their charm before relentless time.

In line 36, the “Moon” is personified as a female.

In lines 52 53, “Death” is personified as a long acquainted companion who would ultimately provide the poet permanent peace.

Simile

In lines 2 3, the poet compares his feelings to having taken poison (hemlock) or consuming a drug (opiate).

In lines 71 72, the word “Forlorn” is compared to a bell.

In line 74, the poet compares fancy to a “deceiving elf” famous for fooling people.

Metaphor

In line 15, the “ warm South” is compared to a beaker.

In line 33, “poesy” or poetry is compared to a bird.

In line 60, the poet compares the nightingale’s song to a “requiem.”

Apostrophe

In line 61, the poet’s direct addressing of the bird is an instance of an apostrophe.

※apostrophe: the symbol ’ used in writing to show when a letter or a number has been left out, as in I'm (= I am) or '85 (= 1985), or that is used before or after s to show possession, as in Helen's house or babies' hands

Onomatopoeia

In line 1 of the first stanza, the poet uses the harsh “t” and “k” sounds of the word “heart aches” and the heavy “d” and “p” sounds of “dull opiate” to suggest his wearied mood.

This is contrasted with the light mood hinted by the usage of such words as, “light winged Dryad” in line 7.

In the last line of the fifth stanza, the poet uses the words, “murmurous haunt” to indicate the subdued tone of the flies.

※Onomatopoeia:

the naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it (such as buzz, hiss)

The meaning of some important words

Provencal song: a region in southern France that is famous for its wine, the sun and lovely lyrics.

Darkling: in the dark

Warm south: a southern drink

Alien corn: the corn is called “alien” as “Ruth” was not an Israelite but a Moabitess

The central idea

The poet, on hearing the song of the nightingale, feels enthralled and desperately wishes to fly away with it. But physical constraints prevent him and he consoles his depressed heart with the estimation that the nightingale is “immortal.” However, as the bird flies away, he is left pondering whether the entire experience had been a reality or a fragment of his imagination. Now, if you want to know more, you may read the stanza wise summary of the poem.

※enthrall: to keep somebody completely interested

Make a sentence→I was always enthralled by the rotary engine, and thought it was a neat idea.

manna

Allusion

The nightingale alludes to Philomela, a character in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, who was turned into a nightingale by the Gods to escape death from the hands of her rapist.

In line 4, the words “lethe wards” allude to the river of forgetfulness, Hades in Greek afterworld that caused memory loss in people that drank water from it.

In line 7, the bird alludes to a female spirit in Greek mythology when it is called a “light-winged Dryad.”

In line 16, the drink alludes to the spring “Hippocrene” that in Greek myth was created by the stamping of the winged horse, “Pegasus.”

In line 32, the poet alludes to the Greek God of wine, “Bacchus” as not responsible for his fanciful escape.

In the lines 63 66, Keats alludes to the Biblical figure, “Ruth” as being a listener of the magnificent song of the nightingale.

Personification

In line 16, the drink is invested living characteristics when it is referred to as “blushing.”

In lines 25 26, the disease “Palsy” is depicted as someone menacingly powerful, capable of causing seizures in men.

In lines 29 30, both “Beauty” and “Love” are said to lose their charm before relentless time.

In line 36, the “Moon” is personified as a female.

In lines 52 53, “Death” is personified as a long acquainted companion who would ultimately provide the poet permanent peace.

Simile

In lines 2 3, the poet compares his feelings to having taken poison (hemlock) or consuming a drug (opiate).

In lines 71 72, the word “Forlorn” is compared to a bell.

In line 74, the poet compares fancy to a “deceiving elf” famous for fooling people.

Metaphor

In line 15, the “ warm South” is compared to a beaker.

In line 33, “poesy” or poetry is compared to a bird.

In line 60, the poet compares the nightingale’s song to a “requiem.”

Apostrophe

In line 61, the poet’s direct addressing of the bird is an instance of an apostrophe.

※apostrophe: the symbol ’ used in writing to show when a letter or a number has been left out, as in I'm (= I am) or '85 (= 1985), or that is used before or after s to show possession, as in Helen's house or babies' hands

Onomatopoeia

In line 1 of the first stanza, the poet uses the harsh “t” and “k” sounds of the word “heart aches” and the heavy “d” and “p” sounds of “dull opiate” to suggest his wearied mood.

This is contrasted with the light mood hinted by the usage of such words as, “light winged Dryad” in line 7.

In the last line of the fifth stanza, the poet uses the words, “murmurous haunt” to indicate the subdued tone of the flies.

※Onomatopoeia:

the naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound associated with it (such as buzz, hiss)

The meaning of some important words

Provencal song: a region in southern France that is famous for its wine, the sun and lovely lyrics.

Darkling: in the dark

Warm south: a southern drink

Alien corn: the corn is called “alien” as “Ruth” was not an Israelite but a Moabitess

The central idea

The poet, on hearing the song of the nightingale, feels enthralled and desperately wishes to fly away with it. But physical constraints prevent him and he consoles his depressed heart with the estimation that the nightingale is “immortal.” However, as the bird flies away, he is left pondering whether the entire experience had been a reality or a fragment of his imagination. Now, if you want to know more, you may read the stanza wise summary of the poem.

※enthrall: to keep somebody completely interested

Make a sentence→I was always enthralled by the rotary engine, and thought it was a neat idea.

manna

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

lease: (is different from"rent"):

to make a legal agreement by which money is paid in order to use land, a building, a vehicle, or a piece of equipment for an agreed period of time

B&M: Brick and Mortar

Brick and mortar (also bricks and mortar or B&M) refers to a physical presence of an organization or business in a building or other structure. The term brick-and-mortar business is often used to refer to a company that possesses or leases retail stores, factory production facilities, or warehouses for its operations.[1] More specifically, in the jargon of e-commerce businesses in the 2000s, brick-and-mortar businesses are companies that have a physical presence (e.g., a retail shop in a building) and offer face-to-face customer experiences.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Brave New World is a story about a futuristic society that has tried to create a perfect community where everyone is happy...

Is it better to be happy ?Or free?

Word:

promiscuous: (=sexual promiscuous)

(of a person) having a lot of different sexual partners or sexual relationships, or (of sexual habits) involving a lot of different partners

Make a sentence→It's a fallacy that gay men are more promiscuous than heterosexuals.

※fallacy:

a brawl is going on→brawl: a noisy, rough, uncontrolled fight

For example: a drunken brawl

Make a sentence→drunken orgies

If you have any request to alter your reproduction of The Orgy c. 1735, you must email us after placing your order and we'll have an artist contact you. If you have another image of The Orgy c. 1735 that you would like the artist to work from, please include it as an attachment. Otherwise, we will reproduce the above image for you exactly as it is.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Raised in this family of scientists, writers, and teachers (his father was a writer and teacher, and his mother a schoolmistress), Huxley received an excellent education, first at home, then at Eton, providing him with access to numerous fields of knowledge. Huxley was an avid student, and during his lifetime he was renowned as a generalist, an intellectual who had mastered the use of the English language but was also informed about cutting-edge developments in science and other fields. Although much of his scientific understanding was superficial—he was easily convinced of findings that remained somewhat on the fringe of mainstream science—his education at the intersection of science and literature allowed him to integrate current scientific findings into his novels and essays in a way that few other writers of his time were able to do.

Aside from his education, another major influence on Huxley’s life and writing was an eye disease contracted in his teenage years that left him almost blind. As a teenager Huxley had dreamed about becoming a doctor, but the degeneration of his eyesight prevented him from pursuing his chosen career. It also severely restricted the activities he could pursue. Because of his near blindness, he depended heavily on his first wife, Maria, to take care of him. Blindness and vision are motifs that permeate much of Huxley’s writing.

After graduating from Oxford in 1916, Huxley began to make a name for himself writing satirical pieces about the British upper class. Though these writings were skillful and gained Huxley an audience and literary name, they were generally considered to offer little depth beyond their lightweight criticisms of social manners. Huxley continued to write prolifically, working as an essayist and journalist, and publishing four volumes of poetry before beginning to work on novels. Without giving up his other writing, beginning in 1921, Huxley produced a series of novels at an astonishing rate: Crome Yellow was published in 1921, followed by Antic Hay in 1923, Those Barren Leaves in 1925, and Point Counter Point in 1928. During these years, Huxley left his early satires behind and became more interested in writing about subjects with deeper philosophical and ethical significance. Much of his work deals with the conflict between the interests of the individual and society, often focusing on the problem of self-realization within the context of social responsibility. These themes reached their zenith in Huxley’s Brave New World, published in 1932. His most enduring work imagined a fictional future in which free will and individuality have been sacrificed in deference to complete social stability.

Brave New World marked a step in a new direction for Huxley, combining his skill for satire with his fascination with science to create a dystopian (anti-utopian) world in which a totalitarian government controlled society by the use of science and technology. Through its exploration of the pitfalls of linking science, technology, and politics, and its argument that such a link will likely reduce human individuality, Brave New World deals with similar themes as George Orwell’s famous novel 1984. Orwell wrote his novel in 1949, after the dangers of totalitarian governments had been played out to tragic effect in World War II, and during the great struggle of the Cold War and the arms race which so powerfully underlined the role of technology in the modern world. Huxley anticipated all of these developments. Hitler came to power in Germany a year after the publication of Brave New World. World War II broke out six years after. The atomic bomb was dropped thirteen years after its publication, initiating the Cold War and what President Eisenhower referred to as a frightening buildup of the “military-industrial complex.” Huxley’s novel seems, in many ways, to prophesize the major themes and struggles that dominated life and debate in the second half of the twentieth century, and continue to dominate it in the twenty-first.

After publishing Brave New World, Huxley continued to live in England, making frequent journeys to Italy. In 1937 Huxley moved to California. An ardent pacifist, he had become alarmed at the growing military buildup in Europe, and determined to remove himself from the possibility of war. Already famous as a writer of novels and essays, he tried to make a living as a screenwriter. He had little success. Huxley never seemed to grasp the requirements of the form, and his erudite literary style did not translate well to the screen.

In the late forties, Huxley started to experiment with hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD and mescaline. He also maintained an interest in occult phenomena, such as hypnotism, séances, and other activities occupying the border between science and mysticism. Huxley’s experiments with drugs led him to write several books that had profound influences on the sixties counterculture. The book he wrote about his experiences with mescaline, The Doors of Perception, influenced a young man named Jim Morrison and his friends, and they named the band they formed The Doors. (The phrase, “the doors of perception” comes from a William Blake poem called The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.) In his last major work, Island, published in 1962, Huxley describes a doomed utopia called Pala that serves as a contrast to his earlier vision of dystopia. A central aspect of Pala’s ideal culture is the use of a hallucinogenic drug called “moksha,” which provides an interesting context in which to view soma, the drug in Brave New World that serves as one tool of the totalitarian state. Huxley died on November 22, 1963, in Los Angeles.

Brave New World belongs to the genre of utopian literature. A utopia is an imaginary society organized to create ideal conditions for human beings, eliminating hatred, pain, neglect, and all of the other evils of the world.

The word utopia comes from Sir Thomas More’s novel Utopia (1516), and it is derived from Greek roots that could be translated to mean either “good place” or “no place.” Books that include descriptions of utopian societies were written long before More’s novel, however. Plato’s Republic is a prime example. Sometimes the societies described are meant to represent the perfect society, but sometimes utopias are created to satirize existing societies, or simply to speculate about what life might be like under different conditions. In the 1920s, just before Brave New World was written, a number of bitterly satirical novels were written to describe the horrors of a planned or totalitarian society. The societies they describe are called dystopias, places where things are badly awry. Either term, utopia or dystopia, could correctly be used to describe Brave New World.

《Amusing Ourselves to Death》

《Amusing Ourselves to Death》

Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1985) is a book by educator Neil Postman. The book's origins lay in a talk Postman gave to the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1984. He was participating in a panel on George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and the contemporary world. In the introduction to his book, Postman said that the contemporary world was better reflected by Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, whose public was oppressed by their addiction to amusement, than by Orwell's work, where they were oppressed by state control.

oppress:

panel:(座談小組)

a small group of people chosen to give advice, make a decision, or publicly discuss their opinions as entertainment

It has been translated into eight languages and sold some 200,000 copies worldwide. In 2005, Postman's son Andrew reissued the book in a 20th anniversary edition. It is regarded as one of the most important texts of media ecology

a cold ,hard truth about what's going on,explained through the words by Neil Postman

The contrast between Aldous Huxley, who is the author of Brave New World,and George Orwell, who wrote 1984.

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books;what Huxley feared was that there would b no reason to ban a book, or there would be no one who would want to read one

Orwell feared those who would deprived us of information; Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism

Orwell feared the truth would be concealed from us; Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.

As Huxley remarked in"Brave New World revisited",the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distraction

money ,object, technology.

irrelevance: (Adj irrelevant)(無關緊要)

the fact that something is not related to what is being discussed or considered and therefore not important, or an example of this

About this painting→

to make a legal agreement by which money is paid in order to use land, a building, a vehicle, or a piece of equipment for an agreed period of time

B&M: Brick and Mortar

Brick and mortar (also bricks and mortar or B&M) refers to a physical presence of an organization or business in a building or other structure. The term brick-and-mortar business is often used to refer to a company that possesses or leases retail stores, factory production facilities, or warehouses for its operations.[1] More specifically, in the jargon of e-commerce businesses in the 2000s, brick-and-mortar businesses are companies that have a physical presence (e.g., a retail shop in a building) and offer face-to-face customer experiences.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Watching "Brave New World"

Is it better to be happy ?Or free?

Word:

promiscuous: (=sexual promiscuous)

(of a person) having a lot of different sexual partners or sexual relationships, or (of sexual habits) involving a lot of different partners

Make a sentence→It's a fallacy that gay men are more promiscuous than heterosexuals.

※fallacy:

a brawl is going on→brawl: a noisy, rough, uncontrolled fight

For example: a drunken brawl

|

| William Hogarth The Orgy c. 1735 |

orgy:

an occasion when a group of people behave in a wild uncontrolled way, especially involving sex, alcohol, or illegal drugsMake a sentence→drunken orgies

About this painting

If you have any request to alter your reproduction of The Orgy c. 1735, you must email us after placing your order and we'll have an artist contact you. If you have another image of The Orgy c. 1735 that you would like the artist to work from, please include it as an attachment. Otherwise, we will reproduce the above image for you exactly as it is.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Content

Aldous Huxley was born in Surrey, England, on July 26, 1894, to an illustrious family deeply rooted in England’s literary and scientific tradition. Huxley’s father, Leonard Huxley, was the son of Thomas Henry Huxley, a well-known biologist who gained the nickname “Darwin’s bulldog” for championing Charles Darwin’s evolutionary ideas. His mother, Julia Arnold, was related to the important nineteenth-century poet and essayist Matthew Arnold.Raised in this family of scientists, writers, and teachers (his father was a writer and teacher, and his mother a schoolmistress), Huxley received an excellent education, first at home, then at Eton, providing him with access to numerous fields of knowledge. Huxley was an avid student, and during his lifetime he was renowned as a generalist, an intellectual who had mastered the use of the English language but was also informed about cutting-edge developments in science and other fields. Although much of his scientific understanding was superficial—he was easily convinced of findings that remained somewhat on the fringe of mainstream science—his education at the intersection of science and literature allowed him to integrate current scientific findings into his novels and essays in a way that few other writers of his time were able to do.

Aside from his education, another major influence on Huxley’s life and writing was an eye disease contracted in his teenage years that left him almost blind. As a teenager Huxley had dreamed about becoming a doctor, but the degeneration of his eyesight prevented him from pursuing his chosen career. It also severely restricted the activities he could pursue. Because of his near blindness, he depended heavily on his first wife, Maria, to take care of him. Blindness and vision are motifs that permeate much of Huxley’s writing.

After graduating from Oxford in 1916, Huxley began to make a name for himself writing satirical pieces about the British upper class. Though these writings were skillful and gained Huxley an audience and literary name, they were generally considered to offer little depth beyond their lightweight criticisms of social manners. Huxley continued to write prolifically, working as an essayist and journalist, and publishing four volumes of poetry before beginning to work on novels. Without giving up his other writing, beginning in 1921, Huxley produced a series of novels at an astonishing rate: Crome Yellow was published in 1921, followed by Antic Hay in 1923, Those Barren Leaves in 1925, and Point Counter Point in 1928. During these years, Huxley left his early satires behind and became more interested in writing about subjects with deeper philosophical and ethical significance. Much of his work deals with the conflict between the interests of the individual and society, often focusing on the problem of self-realization within the context of social responsibility. These themes reached their zenith in Huxley’s Brave New World, published in 1932. His most enduring work imagined a fictional future in which free will and individuality have been sacrificed in deference to complete social stability.

Brave New World marked a step in a new direction for Huxley, combining his skill for satire with his fascination with science to create a dystopian (anti-utopian) world in which a totalitarian government controlled society by the use of science and technology. Through its exploration of the pitfalls of linking science, technology, and politics, and its argument that such a link will likely reduce human individuality, Brave New World deals with similar themes as George Orwell’s famous novel 1984. Orwell wrote his novel in 1949, after the dangers of totalitarian governments had been played out to tragic effect in World War II, and during the great struggle of the Cold War and the arms race which so powerfully underlined the role of technology in the modern world. Huxley anticipated all of these developments. Hitler came to power in Germany a year after the publication of Brave New World. World War II broke out six years after. The atomic bomb was dropped thirteen years after its publication, initiating the Cold War and what President Eisenhower referred to as a frightening buildup of the “military-industrial complex.” Huxley’s novel seems, in many ways, to prophesize the major themes and struggles that dominated life and debate in the second half of the twentieth century, and continue to dominate it in the twenty-first.

After publishing Brave New World, Huxley continued to live in England, making frequent journeys to Italy. In 1937 Huxley moved to California. An ardent pacifist, he had become alarmed at the growing military buildup in Europe, and determined to remove himself from the possibility of war. Already famous as a writer of novels and essays, he tried to make a living as a screenwriter. He had little success. Huxley never seemed to grasp the requirements of the form, and his erudite literary style did not translate well to the screen.

In the late forties, Huxley started to experiment with hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD and mescaline. He also maintained an interest in occult phenomena, such as hypnotism, séances, and other activities occupying the border between science and mysticism. Huxley’s experiments with drugs led him to write several books that had profound influences on the sixties counterculture. The book he wrote about his experiences with mescaline, The Doors of Perception, influenced a young man named Jim Morrison and his friends, and they named the band they formed The Doors. (The phrase, “the doors of perception” comes from a William Blake poem called The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.) In his last major work, Island, published in 1962, Huxley describes a doomed utopia called Pala that serves as a contrast to his earlier vision of dystopia. A central aspect of Pala’s ideal culture is the use of a hallucinogenic drug called “moksha,” which provides an interesting context in which to view soma, the drug in Brave New World that serves as one tool of the totalitarian state. Huxley died on November 22, 1963, in Los Angeles.

Utopias and Dystopias

Brave New World belongs to the genre of utopian literature. A utopia is an imaginary society organized to create ideal conditions for human beings, eliminating hatred, pain, neglect, and all of the other evils of the world.

The word utopia comes from Sir Thomas More’s novel Utopia (1516), and it is derived from Greek roots that could be translated to mean either “good place” or “no place.” Books that include descriptions of utopian societies were written long before More’s novel, however. Plato’s Republic is a prime example. Sometimes the societies described are meant to represent the perfect society, but sometimes utopias are created to satirize existing societies, or simply to speculate about what life might be like under different conditions. In the 1920s, just before Brave New World was written, a number of bitterly satirical novels were written to describe the horrors of a planned or totalitarian society. The societies they describe are called dystopias, places where things are badly awry. Either term, utopia or dystopia, could correctly be used to describe Brave New World.

Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1985) is a book by educator Neil Postman. The book's origins lay in a talk Postman gave to the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1984. He was participating in a panel on George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and the contemporary world. In the introduction to his book, Postman said that the contemporary world was better reflected by Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, whose public was oppressed by their addiction to amusement, than by Orwell's work, where they were oppressed by state control.

oppress:

panel:(座談小組)

a small group of people chosen to give advice, make a decision, or publicly discuss their opinions as entertainment

It has been translated into eight languages and sold some 200,000 copies worldwide. In 2005, Postman's son Andrew reissued the book in a 20th anniversary edition. It is regarded as one of the most important texts of media ecology

a cold ,hard truth about what's going on,explained through the words by Neil Postman

The contrast between Aldous Huxley, who is the author of Brave New World,and George Orwell, who wrote 1984.

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books;what Huxley feared was that there would b no reason to ban a book, or there would be no one who would want to read one

Orwell feared those who would deprived us of information; Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism

Orwell feared the truth would be concealed from us; Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.

As Huxley remarked in"Brave New World revisited",the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distraction

money ,object, technology.

irrelevance: (Adj irrelevant)(無關緊要)

the fact that something is not related to what is being discussed or considered and therefore not important, or an example of this

Orwell feared that we will become a captive culture; Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture ,preoccupied with some equivalent of The Feelies ,the Orgy Porgy,and the centrifugal bumblepuppy

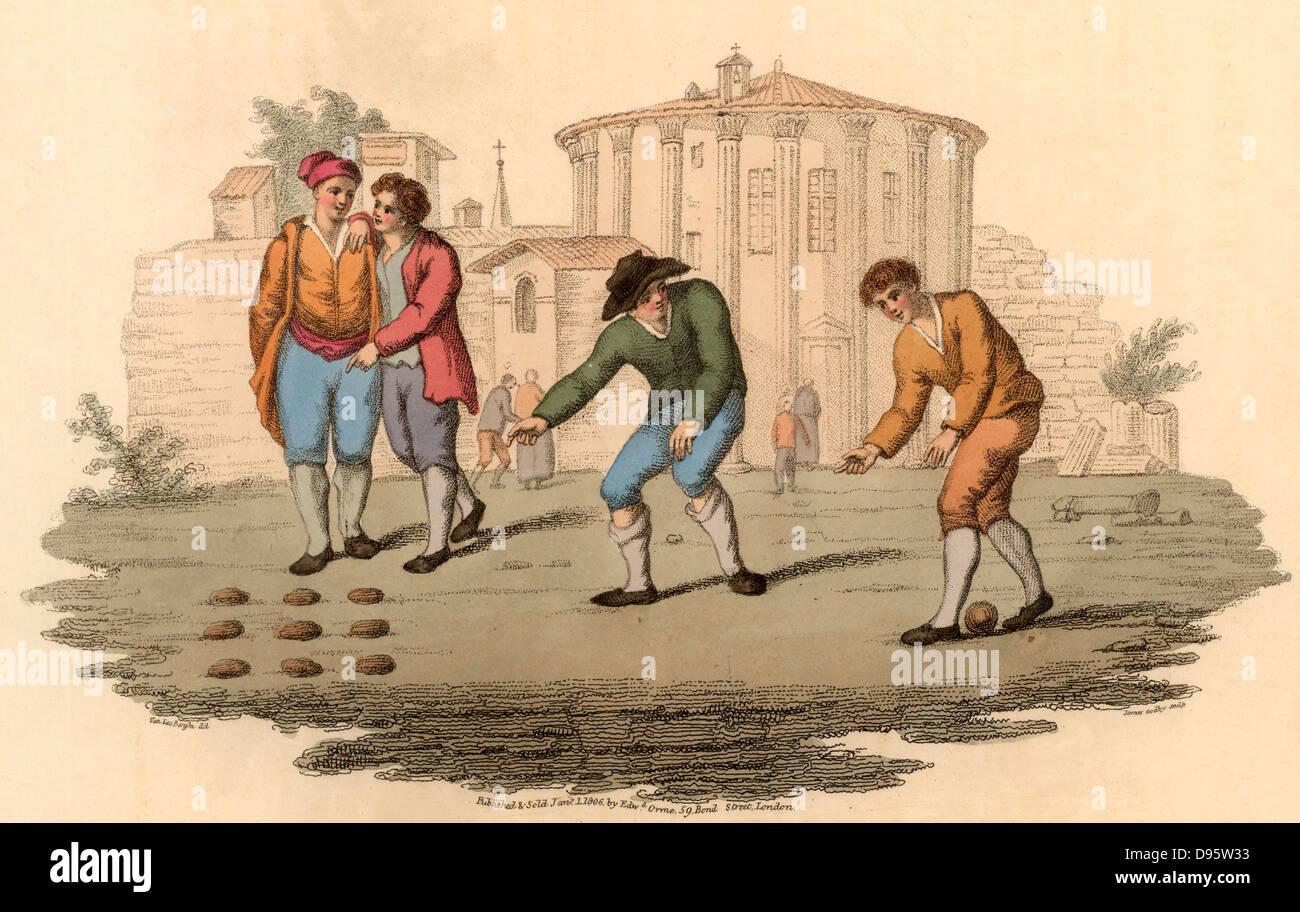

bumblepuppy:  |

| Youths play bumble puppy |

Youths playing Bumble Puppy, or Nine Holes near the Templa of Vesta, Rome, Italy. To set up the game, the young men cut nine holes in the turf large enough to take the ball. Money is staked and if a player does not pitch the ball into a hole, he loses his stake. When a player pitches the ball into the centre hole, he takes all the money staked and a new game is begun. Hand coloured lithograph from 'Italian Scenery, Manners and Customs' by Buon Airetti (London, 1806).

Centrifugal Bumble-Puppy

An advanced, consumerist form of tetherball played by the children in Aldous Huxley's novel, Brave New World.

You can't play Electro-magnetic Golf according to the rules of Centrifugal Bumble-puppy.

At Forbes, one contributor wrote that the book “may help explain the otherwise inexplicable”. CNN noted that Trump’s allegedly shocking “ascent would not have surprised Postman”. At ChristianPost.com, Richard D Land reflected on reading the book three decades ago and feeling “dumbfounded … by Postman’s prophetic insights into what was then America’s future and is now too often a painful description of America’s present”. Last month, a headline at Paste Magazine asked: “Did Neil Postman Predict the Rise of Trump and Fake News?”

Colleagues and former students of my father, who taught at New York University for more than 40 years and who died in 2003, would now and then email or Facebook message me, after the latest Trumpian theatrics, wondering, “What would Neil think?” or noting glumly, “Your dad nailed it.”

The misplaced focus on Orwell was understandable: after all, for decades the cold war had made communism – as embodied by Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Big Brother – the prime existential threat to America and to the greatest of American virtues, freedom. And, to put a bow on it, the actual year, 1984, was fast approaching when my father was writing his book, so we had Orwell’s powerful vision on the brain.

Advertisement

Whoops. Within a half-decade, the Berlin Wall came down. Two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed.

“We were keeping our eye on 1984,” my father wrote. “When the year came and the prophecy didn’t, thoughtful Americans sang softly in praise of themselves. The roots of liberal democracy had held. Wherever else the terror had happened, we, at least, had not been visited by Orwellian nightmares.”

Unfortunately, there remained a vision we Americans did need to guard against, one that was percolating right then, in the 1980s. The president was a former actor and polished communicator. Our political discourse (if you could call it that) was day by day diminished to soundbites (“Where’s the beef?” and “I’m paying for this microphone” became two “gotcha” moments, apparently testifying to the speaker’s political formidableness).

The nation increasingly got its “serious” information not from newspapers, which demand a level of deliberation and active engagement, but from television: Americans watched an average of 20 hours of TV a week. (My father noted that USA Today, which launched in 1982 and featured colorized images, quick-glance lists and charts, and much shorter stories, was really a newspaper mimicking the look and feel of TV news.)

But it wasn’t simply the magnitude of TV exposure that was troubling. It was that the audience was being conditioned to get its information faster, in a way that was less nuanced and, of course, image-based. As my father pointed out, a written sentence has a level of verifiability to it: it is true or not true – or, at the very least, we can have a meaningful discussion over its truth. (This was pre-truthiness, pre-“alternative facts”.)

But an image? One never says a picture is true or false. It either captures your attention or it doesn’t. The more TV we watched, the more we expected – and with our finger on the remote, the more we demanded – that not just our sitcoms and cop procedurals and other “junk TV” be entertaining but also our news and other issues of import. Digestible. Visually engaging. Provocative. In short, amusing. All the time. Sorry, C-Span.

This was, in spirit, the vision that Huxley predicted way back in 1931, the dystopia my father believed we should have been watching out for. He wrote:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture.

1984 – the year, not the novel – looks positively quaint now. One-third of a century later, we all carry our own personalized screens on us, at all times, and rather than seven broadcast channels plus a smattering of cable, we have a virtual infinity of options.

Advertisement

Today, the average weekly screen time for an American adult – brace yourself; this is not a typo – is 74 hours (and still going up). We watch when we want, not when anyone tells us, and usually alone, and often while doing several other things. The soundbite has been replaced by virality, meme, hot take, tweet. Can serious national issues really be explored in any coherent, meaningful way in such a fragmented, attention-challenged environment?

Sure, times change. Technology and innovation wait for no man. Get with the program. But how engaged can any populace be when the most we’re asked to do is to like or not like a particular post, or “sign” an online petition? How seriously should anyone take us, or should we take ourselves, when the “optics” of an address or campaign speech – raucousness, maybe actual violence, childishly attention-craving gestures or facial expressions – rather than the content of the speech determines how much “airtime” it gets, and how often people watch, share and favorite it?

My father’s book warned of what was coming, but others have seen and feared aspects of it, too (Norbert Wiener, Sinclair Lewis, Marshall McLuhan, Jacques Ellul, David Foster Wallace, Sherry Turkle, Douglas Rushkoff, Naomi Klein, Edward Snowden, to name a few).

Our public discourse has become so trivialized, it’s astounding that we still cling to the word “debates” for what our presidential candidates do onstage when facing each other. Really? Who can be shocked by the rise of a reality TV star, a man given to loud, inflammatory statements, many of which are spectacularly untrue but virtually all of which make for what used to be called “good television”?

Who can be appalled when the coin of the realm in public discourse is not experience, thoughtfulness or diplomacy but the ability to amuse – no matter how maddening or revolting the amusement?

So, yes, my dad nailed it. Did he also predict that the leader we would pick for such an age, when we had become perhaps terminally enamored of our technologies and amusements, would almost certainly possess fascistic tendencies? I believe he called this, too.

For all the ways one can define fascism (and there are many), one essential trait is its allegiance to no idea of right but its own: it is, in short, ideological narcissism. It creates a myth that is irrefutable (much in the way that an image’s “truth” cannot be disproved), in perpetuity, because of its authoritarian, unrestrained nature.

“Television is a speed-of-light medium, a present-centered medium,” my father wrote. “Its grammar, so to say, permits no access to the past … history can play no significant role in image politics. For history is of value only to someone who takes seriously the notion that there are patterns in the past which may provide the present with nourishing traditions.”

Later in that passage, Czesław Miłosz, winner of the Nobel prize for literature, is cited for remarking in his 1980 acceptance speech that that era was notable for “a refusal to remember”; my father notes Miłosz referencing “the shattering fact that there are now more than one hundred books in print that deny that the Holocaust ever took place”.

Again: how quaint.

While fake news has been with us as long as there have been agendas, and from both sides of the political aisle, we’re now witnessing – thanks to Breitbart News, Infowars and perpetuation of myths like the one questioning Barack Obama’s origins – a sort of distillation, a fine-tuning.

“An Orwellian world is much easier to recognize, and to oppose, than a Huxleyan,” my father wrote. “Everything in our background has prepared us to know and resist a prison when the gates begin to close around us … [but] who is prepared to take arms against a sea of amusements?”

I wish I could tell you that, for all his prescience, my father also supplied a solution. He did not. He saw his job as identifying a serious, under-addressed problem, then asking a set of important questions about the problem. He knew it would be hard to find an easy answer to the damages wrought by “technopoly”. It was a systemic problem, one baked as much into our individual psyches as into our culture.

But we need more than just hope for a way out. We need a strategy, or at least some tactics.

First: treat false allegations as an opportunity. Seek information as close to the source as possible. The internet represents a great chance for citizens to do their own hunting – there’s ample primary source material, credible eyewitnesses, etc, out there – though it can also be manipulated to obfuscate that. No one’s reality, least of all our collective one, should be a grotesque game of telephone.

Second: don’t expect “the media” to do this job for you. Some of its practitioners do, brilliantly and at times heroically. But most of the media exists to sell you things. Its allegiance is to boosting circulation, online traffic, ad revenue. Don’t begrudge it that. But then don’t be suckered about the reasons why Story X got play and Story Y did not.

Third: for journalists, Jay Rosen, a former student of my father’s and a leading voice in the movement known as “public journalism”, offers several useful, practical suggestions.

Finally, and most importantly, it should be the responsibility of schools to make children aware of our information environments, which in many instances have become our entertainment environments, but there is little evidence that schools are equipped or care to do this. So someone has to.

We must teach our children, from a very young age, to be skeptics, to listen carefully, to assume everyone is lying about everything. (Well, maybe not everyone.) Check sources. Consider what wasn’t said. Ask questions. Understand that every storyteller has a bias – and so does every platform.

We all laughed – some of us, anyway – at Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert’s version of the news, to some extent because everything had become a joke. If we wish not to be “soma”-tized (Huxley’s word) by technology, to be something less than smiling idiots and complicit in the junking of our own culture, then “what is required of us now is a new era of responsibility … giving our all to a difficult task. This is the price and the promise of citizenship.”

My father didn’t write those last words – our recently retired president said them in his final inaugural address. He’s right. It will be difficult. It’s not so amusing any more.

Comments

Post a Comment